High Lipoprotein(a): Causes, Risks, and Treatment Options

Jan 18, 2023

Lipoprotein(a): The "Hidden" Genetic Cholesterol That Could Be Putting You at Risk

One of the most common topics and questions I get at medical conferences is, "Can you tell us more about lipoprotein little a?"

What is lipoprotein a and what can we do about it?

What is my life expectancy with lipoprotein a?

Lipoprotein little a, commonly known as Lp(a) or LPa. It is a type of lipoprotein that carries cholesterol and other fats through the bloodstream. Lp(a) is considered one of the most dangerous and potent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, aortic stenosis, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, and other related conditions.

Let's dive deep and discuss the structure, function, and medical significance of Lp(a), including its effects on health and how it can be managed and treated.

Structure of Lipoprotein Little a (LPa)

Lipoprotein(a) is composed of two primary components, the apoB-100 protein, and a glycoprotein called apolipoprotein(a). The apoB-100 protein is found in low-density lipoprotein (LDL), which is often referred to as "bad" cholesterol. The apoB-100 protein is found on all LDL particles and all other atherogenic particles, and hence it's a good marker for disease and atherogenicity. The higher the ApoB, the more atherosclerosis you are going to have.

Apolipoprotein(a) is similar in structure to plasminogen, a protein involved in blood clotting. Lp(a) is unique in that it contains a kringle domain, which is a type of protein domain found in many blood-clotting factors. See the diagram above.

The size of Lp(a) can vary, and there are several isoforms, which differ in the number of kringle domains present. The number of kringle domains appears to be an important determinant of Lp(a) function and may influence its potential to cause disease and atherogenicity.

Function of Lipoprotein(a)

The function of Lp(a) is not entirely clear, but it is thought to play a role in the regulation of blood clotting. Lp(a) has been shown to inhibit the breakdown of blood clots by binding to plasminogen, which prevents it from converting to plasmin, an enzyme that dissolves blood clots. This mechanism may be important in preventing excessive bleeding but may also contribute to the formation of blood clots and blockages in the arteries.

Above is a lipoprotein little a particle with the Kringle chain on the outside.

Medical Significance of Lipoprotein(a)

High levels of Lp(a) in the blood have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, aortic valve disease, and other related conditions. Lp(a) appears to contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, a condition in which plaque builds up in the arteries, causing them to narrow and harden. This can lead to reduced blood flow to the heart, brain, and other organs, increasing the risk of heart attacks, strokes, aortic stenosis, peripheral artery disease, and other serious complications.

Look at the table below. Your chance of having a heart attack is 3-4 times higher. The chance of having aortic stenosis (tight aortic valve) is 3 times higher. The risk of coronary artery atherosclerosis is 5 times higher. The risk of atherosclerosis in any other arterial bed (carotid, iliac, femoral, strokes) are also 1-2 times higher. The risk of heart failure is 1.5 to 2 times higher.

Because LP(a) significantly increases the risk of these diseases, we must take this very seriously.

Studies on Lipoprotein a

Several studies have shown that individuals with high levels of Lp(a) are at an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, even when other risk factors are taken into account. For example, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that individuals with Lp(a) levels in the top 20% of the population had a 70% increased risk of developing coronary heart disease compared to those in the bottom 20%. (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0902604)

Lipoprotein a And Stroke Risk

Lp(a) has also been associated with an increased risk of stroke, particularly in individuals with a history of high blood pressure or smoking. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that individuals with high levels of Lp(a) were at a 2.5-fold increased risk of developing ischemic stroke compared to those with low levels. (https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/184315)

More Recent JAMA Evidence Shows Stronger Associations

More recent studies have found stronger associations than the original 2009 meta-analysis. A 2024 JAMA Cardiology study examining pooled data from multiple U.S. cohorts found that among individuals without baseline atherosclerotic disease, those in the highest Lp(a) percentile (91st-100th) had a 75% increased hazard of ischemic stroke (HR 1.75, P = 0.016) compared to the reference group.

Similarly, a 2025 study in The Lancet Neurology examining 30-year stroke risk in healthy women found that women in the highest lipoprotein(a) quintile had a 27% increased risk of ischemic stroke (HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.05-1.55) compared to the lowest quintile. When participants who initiated statin therapy were censored, this association strengthened to a 55% increased risk (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.18-2.03).

Source:

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/184315

Is Lipoprotein(a) 3-6 Times More Atherogenic Than LDL Cholesterol?

Yes, lipoprotein(a) is approximately 6-fold more atherogenic than LDL on a per-particle basis, based on recent apolipoprotein B-based genetic analyses. This substantially greater atherogenicity has critical implications for cardiovascular risk assessment and the potential impact of Lp(a)-lowering therapies currently in development.

The Evidence for 6-Fold Greater Atherogenicity

A landmark 2024 genetic analysis published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology leveraged the fact that both Lp(a) and LDL contain exactly one apolipoprotein B (apoB) molecule per particle to directly compare their relative atherogenicity. Using genome-wide association studies in the UK Biobank population, investigators identified two distinct clusters of genetic variants: 107 variants linked to Lp(a) mass concentration and 143 variants linked to LDL concentration.

The Mendelian randomization analysis revealed that for a 50 nmol/L higher Lp(a)-apoB, the odds ratio for coronary heart disease was 1.28 (95% CI: 1.24-1.33) compared with only 1.04 (95% CI: 1.03-1.05) for the same increment in LDL-apoB. From these data, the investigators estimated that the atherogenicity of Lp(a) is approximately 6.6-fold (95% CI: 5.1-8.8) greater than that of LDL on a per-particle basis.

This finding has been corroborated by multiple independent sources. A 2025 review in Circulation states that "on an equimolar basis, Lp(a) is ~5 to 6 times more atherogenic than particles that have been widely associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, such as LDL". Similarly, a 2025 review in Current Opinion in Lipidology notes that "genetic evidence reveals that Lp(a) is six-fold more atherogenic per particle than LDL".

Source:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38233012/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39928714/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40748007/

Management and Treatment of Lipoprotein(a)

Currently, there are no specific treatments for high Lp(a) levels. Lifestyle modifications, such as a healthy diet and regular exercise, may help to lower Lp(a) levels, as well as other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Some medications, such as niacin and estrogen, may also be effective in reducing Lp(a) levels, but their use in this context is still under investigation.

With that said, individuals with high Lp(a) are at the highest risk, and hence, I recommend lowering LDL cholesterol to below 40 mg/dL. This is in line with the current European Atherosclerotic Society Guidelines and the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guidelines on treating those in the highest risk categories.

Unfortunately, niacin has only shown a very modest decrease and is very difficult to take due to severe side effects, liver toxicity, and it has been shown to make your HDL more atherogenic. Niacin has not reduced cardiovascular outcomes (heart attacks, strokes, death rates) in multiple major trials. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34134520/ , https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6481429/ , https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22085343/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25014686/, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109722055942, )

While there is no specific treatment to lower Lp(a) levels, lifestyle modifications, such as a healthy diet, exercise, and weight loss, may help to lower overall cardiovascular risk. In addition, there are medications available that can help lower Lp(a) levels, including statins, ezetimibe, and PCSK9 inhibitors.

Statins, such as Crestor (rosuvastatin), have been shown to modestly reduce Lp(a) levels, but in other studies, has actually shown to increase Lp(a) by 10%, but still reduced CVD by 28%. In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Lipidology, treatment with rosuvastatin was associated with a 20% reduction in Lp(a) levels over 12 weeks in individuals with high Lp(a) levels (1). However, the magnitude of the reduction varied widely among individuals. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8436116/ , https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3946056/

Ezetimibe (Zetia) is another medication that has been shown to modestly lower Lp(a) levels. In a study published in the Journal of Lipid Research, treatment with ezetimibe was associated with a 9% reduction in Lp(a) levels over 12 weeks in individuals with high Lp(a) levels (2). https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/184063

PCSK9 inhibitors, such as Repatha (evolocumab), are a newer class of medications that have been shown to significantly lower Lp(a) levels. In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, treatment with evolocumab was associated with a 27% reduction in Lp(a) levels over 12 weeks in individuals with high Lp(a) levels (3). https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa1615664

There are newer medications that are in phase 3 trials that show a lot of promise in lowering LP(a). Full discussion on these below. But one such medication is hepatocyte-directed antisense oligonucleotide AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx, referred to here as APO(a)-LRx that showed up to an 80% reduction in LP(a). (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1905239)

It is important to note that while these medications may help to lower Lp(a) levels, their overall impact on cardiovascular risk reduction is still being studied. Individuals with high Lp(a) levels should work with their healthcare providers to determine the best treatment options for managing their overall cardiovascular risk.

The Role of Aspirin in Managing Elevated Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Risk

Aspirin is not currently recommended for primary prevention based solely on elevated lipoprotein(a) levels, though emerging evidence suggests individuals with Lp(a) >50 mg/dL may represent a subgroup where cardiovascular benefits outweigh bleeding risks, particularly when combined with other high-risk features.

Emerging Evidence for Potential Benefit

Several recent observational studies and post hoc analyses suggest aspirin may specifically benefit individuals with elevated Lp(a). In the ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial, among 12,815 genotyped participants, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 11.4 events per 1,000 person-years in carriers of the rs3798220-C variant (associated with highly elevated Lp(a)) without significantly increased bleeding risk, indicating a shift toward net benefit. Similarly, the Women's Health Study found that women carrying this variant had approximately 2-fold higher cardiovascular risk, with risk reduction observed only in those randomized to aspirin.

More recent studies using measured plasma Lp(a) levels have extended these genetic findings. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a propensity-matched analysis found that aspirin use was associated with approximately 50% reduction in coronary heart disease events among participants with Lp(a) >50 mg/dL (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32-0.94), with those using aspirin having similar risk as individuals with Lp(a) ≤50 mg/dL regardless of aspirin use.

Conflicting Evidence and Limitations On Aspirin

However, not all studies have confirmed these findings. A 2025 multicohort analysis pooling data from ARIC, CHS, and MESA studies (23,662 participants) found no evidence that aspirin's association with cardiovascular disease differed by Lp(a) levels. Using propensity score matching, the hazard ratio for cardiovascular disease associated with aspirin use was 1.12 (95% CI 0.96-1.31) in those with high Lp(a) and 1.04 (95% CI 0.96-1.13) in those with low Lp(a) (p-value comparing HRs: 0.38), suggesting no differential benefit.

These conflicting results highlight critical limitations in the current evidence base. Most data come from post hoc analyses or observational studies rather than prospective randomized trials specifically designed to test aspirin in individuals with elevated Lp(a). The genetic studies focused on narrow subsets carrying specific variants (rs3798220-C affects only 3.5% of Europeans), and genetic risk scores account for at most 60% of plasma Lp(a) variation. Plasma Lp(a) levels—which directly interact with the coagulation system and platelets—would be expected to be more informative than genotypes alone.

Biological Rationale For Aspirin

The theoretical basis for aspirin's potential benefit in elevated Lp(a) stems from Lp(a)'s prothrombotic properties and interactions with the fibrinolytic system and platelets. In vitro and in vivo studies suggest aspirin may lower serum Lp(a) levels, though this effect is modest and inconsistent. The prothrombotic nature of Lp(a) may also explain why elevated Lp(a) was not associated with higher bleeding risk in some studies, potentially improving the benefit-risk balance for aspirin.

Current Clinical Guidance For Aspirin

No current guidelines recommend aspirin for primary prevention based solely on elevated Lp(a). The 2024 Lancet review on lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease states explicitly: "No evidence or guidelines advise the use of aspirin for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the primary prevention setting for people with high lipoprotein(a)." However, aspirin should be used in individuals with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease following standard secondary prevention guidelines.

When elevated Lp(a) is combined with other high-risk features, aspirin may be considered as part of shared decision-making. Individuals with both elevated Lp(a) (≥50 mg/dL) and elevated coronary artery calcium (≥100 Agatston units) have >20% cumulative 10-year cardiovascular risk—approaching secondary prevention rates—and aspirin therapy may be considered in these individuals after weighing bleeding risk. Notably, among individuals with coronary artery calcium score of 0, elevated Lp(a) failed to stratify 10-year cardiovascular risk, suggesting CAC scoring may help identify which high-Lp(a) individuals might benefit most from aspirin.

Aspirin Lp(a) Bottom Line

While emerging evidence suggests aspirin may specifically reduce cardiovascular events in individuals with elevated Lp(a)—particularly those with levels >50 mg/dL—the data remain insufficient to support routine aspirin use for primary prevention based on Lp(a) alone. The conflicting results from recent studies, reliance on post hoc analyses rather than prospective randomized trials, and lack of studies using measured plasma Lp(a) levels as the primary stratification variable all limit definitive conclusions.

In clinical practice, decisions about aspirin in individuals with elevated Lp(a) should involve shared decision-making, balancing potential cardiovascular benefits against bleeding risks, and considering the presence of other risk enhancers such as elevated coronary artery calcium. Future randomized controlled trials specifically enrolling individuals with elevated plasma Lp(a) levels and randomizing aspirin use are needed to provide definitive guidance for this population, particularly given the current lack of approved Lp(a)-lowering therapies.

Comparing Aspirin to Emerging RNA-Based Therapies for Elevated Lipoprotein(a): What Role for Aspirin Until Targeted Treatments Arrive?

Aspirin may provide modest cardiovascular benefit (approximately 50% relative risk reduction in select studies) in individuals with elevated Lp(a) >50 mg/dL, while emerging RNA-based therapies promise 80-98% Lp(a) reductions—but lack outcome data. Until results from ongoing phase 3 trials become available, aspirin represents the only widely accessible intervention that may specifically address Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular risk in primary prevention, though its use requires careful risk-benefit assessment.

The Clinical Context: A Prevalent Risk Factor Without Approved Treatment

Lipoprotein(a) is a genetically determined, causal risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic valve stenosis, affecting approximately 20-25% of the global population at levels ≥50 mg/dL. Unlike LDL cholesterol—for which causality is supported by both human genetics and randomized trials—evidence for Lp(a) causality comes primarily from human genetics, as no outcome trials have yet demonstrated that specifically lowering Lp(a) reduces cardiovascular events. This creates a therapeutic vacuum: millions of individuals face elevated cardiovascular risk from high Lp(a), yet no FDA-approved pharmacologic therapies exist specifically for Lp(a) lowering to prevent cardiovascular disease.

Aspirin's Potential Role: Emerging but Incomplete Evidence

Recent studies suggest aspirin may specifically benefit individuals with elevated Lp(a), with the strongest evidence in those with levels >50 mg/dL. In the ASPREE trial, among 12,815 genotyped participants, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 11.4 events per 1,000 person-years in carriers of the rs3798220-C variant (associated with highly elevated Lp(a)) without significantly increased bleeding risk, indicating a shift toward net benefit. The Women's Health Study similarly found that women carrying this variant had approximately 2-fold higher cardiovascular risk, with risk reduction observed only in those randomized to aspirin.

More clinically applicable, a propensity-matched analysis from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) using measured plasma Lp(a) levels found that aspirin use was associated with approximately 50% reduction in coronary heart disease events among participants with Lp(a) >50 mg/dL (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32-0.94), with those using aspirin having similar risk as individuals with Lp(a) ≤50 mg/dL regardless of aspirin use.

However, critical limitations temper these findings. Most data come from post hoc analyses or observational studies rather than prospective randomized trials specifically designed to test aspirin in individuals with elevated Lp(a). The genetic studies focused on narrow subsets carrying specific variants (rs3798220-C affects only 3.5% of Europeans), and genetic risk scores account for at most 60% of plasma Lp(a) variation. Plasma Lp(a) levels—which directly interact with the coagulation system and platelets—would be expected to be more informative than genotypes alone.

RNA-Based Therapies: Dramatic Biochemical Reductions Awaiting Clinical Validation

The most promising therapeutic developments are RNA-based agents that achieve 80-98% sustained Lp(a) reductions through gene silencing of the LPA gene. These include antisense oligonucleotides (pelacarsen) and small interfering RNAs (olpasiran, lepodisiran, zerlasiran, SLN360).

Pelacarsen inhibits mRNA production from the LPA gene in hepatocyte nuclei and is administered by once-monthly subcutaneous injection, achieving approximately 80% Lp(a) reduction. Olpasiran, lepodisiran, and zerlasiran inhibit mRNA production within the cytosol of hepatocytes and are injected subcutaneously two to four times yearly, achieving up to 98% reductions. An alternative approach, muvalaplin, inhibits the attachment of apolipoprotein(a) to apolipoprotein B on LDL particles and achieves approximately 65% reduction with daily oral administration.

Large cardiovascular outcomes trials are currently underway to determine whether these dramatic biochemical reductions translate into meaningful clinical benefits. The Lp(a) HORIZON trial (NCT04023552) of pelacarsen has enrolled 8,323 patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and Lp(a) ≥70 mg/dL, with a primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and urgent coronary revascularization. Olpasiran and lepodisiran are also being studied in phase 3 cardiovascular outcome trials.

Comparing Potential Benefits: What the Evidence Suggests

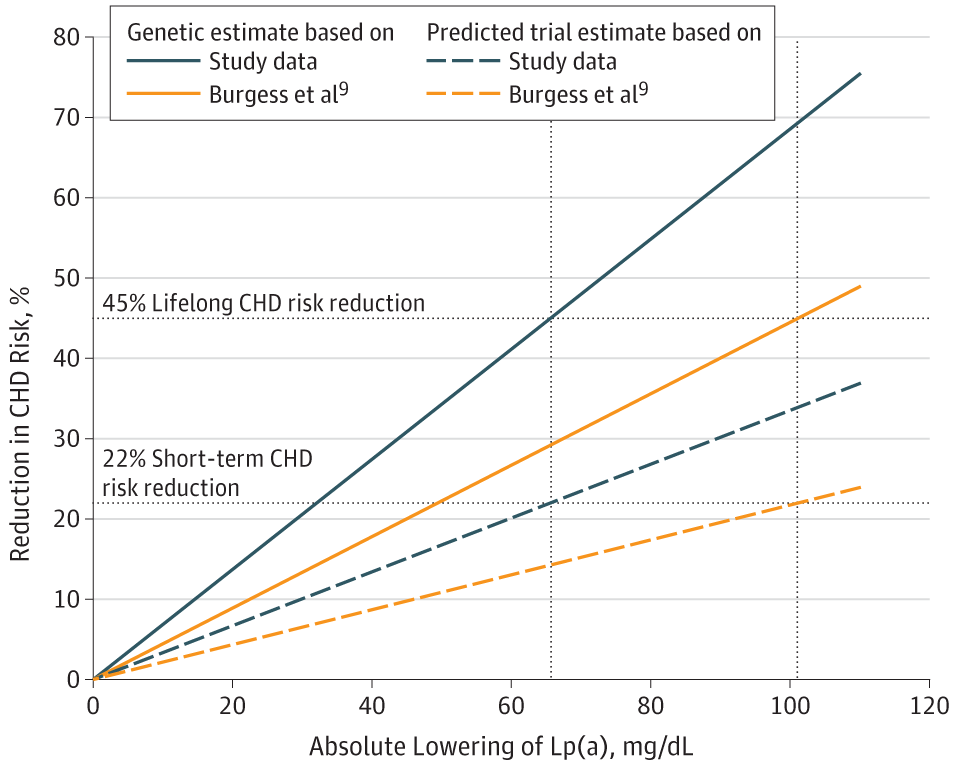

Direct comparison between aspirin and RNA-based therapies is impossible without head-to-head trials, but Mendelian randomization analyses provide insight into the magnitude of Lp(a) lowering required for clinical benefit. A 2019 analysis estimated that a 65.7 mg/dL reduction in Lp(a) would be needed to match the coronary heart disease risk reduction achieved by lowering LDL-C by 38.67 mg/dL (approximately 22% risk reduction in short-term trials).

Figure 2. Estimates of Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Risk Reduction With Lowering of Lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) Concentration

Estimation of the Required Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapeutic Effect Size for Reduction in Coronary Heart Disease Outcomes: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. JAMA Cardiol. May 31, 2019.

This suggests that the 80-98% Lp(a) reductions achieved by RNA-based therapies—which in absolute terms could represent 40-100+ mg/dL reductions in individuals with baseline Lp(a) of 50-100 mg/dL—should theoretically provide substantial cardiovascular benefit if the Mendelian randomization estimates are accurate. By contrast, aspirin does not lower Lp(a) levels (or does so only modestly and inconsistently), so any benefit would derive from antiplatelet effects interacting with Lp(a)'s prothrombotic properties rather than from Lp(a) reduction itself.

The approximately 50% relative risk reduction observed with aspirin in MESA participants with Lp(a) >50 mg/dL is striking but comes from observational data subject to residual confounding.[6] If confirmed in randomized trials, this magnitude of benefit would be clinically meaningful—but the absolute event reduction depends on baseline risk. In ASPREE, aspirin reduced events by 11.4 per 1,000 person-years in rs3798220-C carriers, a substantial absolute benefit in this high-risk genetic subgroup.

The Role of Aspirin Until Targeted Therapies Become Available

Current guidelines do not recommend aspirin for primary prevention based solely on elevated Lp(a), as no randomized trials have directly addressed this question. However, in the absence of approved Lp(a)-lowering therapies, aspirin represents the only widely accessible intervention that may specifically address Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular risk.

Several considerations support selective aspirin use in high-risk individuals with elevated Lp(a) pending availability of RNA-based therapies:

Biological plausibility: Lp(a)'s prothrombotic properties and interactions with the fibrinolytic system and platelets provide mechanistic rationale for aspirin benefit. The prothrombotic nature of Lp(a) may also explain why elevated Lp(a) was not associated with higher bleeding risk in some studies, potentially improving the benefit-risk balance.

Emerging clinical evidence: While not definitive, multiple independent analyses (ASPREE, Women's Health Study, MESA) suggest benefit in individuals with elevated Lp(a), with consistency across genetic and measured Lp(a) approaches.

Accessibility and cost: Aspirin is widely available, well-tolerated, and low-cost, making it practical for widespread use while awaiting RNA-based therapies that will likely be expensive and require specialized administration.

Time horizon: RNA-based therapies remain years away from approval. The Lp(a) HORIZON trial and other phase 3 studies will not report results until the late 2020s at earliest. During this interval, individuals with elevated Lp(a) face ongoing cardiovascular risk.

In clinical practice, aspirin decisions in individuals with elevated Lp(a) should involve shared decision-making, balancing potential cardiovascular benefits against bleeding risks, and considering the presence of other risk enhancers such as elevated coronary artery calcium.[4-7] Individuals with both elevated Lp(a) (≥50 mg/dL) and elevated coronary artery calcium (≥100 Agatston units) have >20% cumulative 10-year cardiovascular risk—approaching secondary prevention rates—and aspirin therapy may be particularly reasonable in these individuals after weighing bleeding risk.

What Happens When RNA-Based Therapies Arrive?

If ongoing trials demonstrate that RNA-based Lp(a)-lowering therapies reduce cardiovascular events, they will likely supersede aspirin as the preferred intervention for high-risk individuals with elevated Lp(a). The magnitude of Lp(a) reduction (80-98%) far exceeds what can be achieved with any currently available therapy, and if Mendelian randomization estimates are accurate, this should translate into substantial cardiovascular benefit.

However, several scenarios could preserve a role for aspirin even after RNA-based therapies become available:

- Cost and access limitations: RNA-based therapies will likely be expensive and may not be accessible to all patients who could benefit

- Combination therapy: Aspirin's antiplatelet effects may provide additive benefit beyond Lp(a) lowering alone

- Intermediate-risk populations: RNA-based therapies may be reserved for highest-risk individuals, leaving aspirin as an option for those with moderately elevated Lp(a)

- Negative trial results: If phase 3 trials fail to demonstrate cardiovascular benefit despite dramatic Lp(a) lowering, aspirin might remain the only intervention with suggestive (albeit incomplete) evidence of benefit

Critical Knowledge Gaps

Direct randomized controlled trials comparing aspirin to placebo in individuals with elevated plasma Lp(a) levels are urgently needed. Such trials should enroll participants based on measured Lp(a) levels (not just genetic variants), include diverse populations, and have adequate power to assess both cardiovascular benefits and bleeding risks. Similarly, once RNA-based therapies demonstrate efficacy, head-to-head comparisons or trials of combination therapy would clarify optimal management strategies.

The Bottom Line On Aspirin and Emerging RNA Based Therapies

Aspirin may provide meaningful cardiovascular benefit in individuals with elevated Lp(a) >50 mg/dL, with observational data suggesting approximately 50% relative risk reduction in select populations. While this evidence is incomplete and guidelines do not currently recommend aspirin solely for elevated Lp(a), the absence of approved targeted therapies creates a therapeutic void that aspirin—a widely available, low-cost intervention—may partially fill through shared decision-making in high-risk individuals.

Emerging RNA-based therapies promise 80-98% Lp(a) reductions that, if translated into proportional cardiovascular benefit, would far exceed aspirin's potential impact. However, these therapies remain years away from approval, and their ultimate efficacy, safety, cost, and accessibility remain uncertain. Until results from ongoing phase 3 trials become available, aspirin represents a reasonable consideration for primary prevention in carefully selected individuals with elevated Lp(a), particularly those with additional high-risk features such as elevated coronary artery calcium, after thorough discussion of potential benefits and bleeding risks.

The next several years will be transformative for Lp(a) management, with definitive answers expected from both aspirin observational studies and RNA-based therapy outcome trials. In the interim, clinicians must navigate uncertainty, balancing the desire to address a prevalent, genetically determined cardiovascular risk factor against the limitations of current evidence and the promise of more effective therapies on the horizon.

Lipoprotein Little a Conclusion

Lipoprotein(a) is a unique lipoprotein that carries cholesterol and other fats through the bloodstream. It appears to play a role in the regulation of blood clotting, but high levels of Lp(a) in the blood have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and other related conditions. While there are no specific current treatments for high Lp(a) levels, lifestyle modifications and certain medications may help to lower levels and reduce overall risk for related conditions.

There are a few medications in phase III trial that look very promising causing up to an 80% reduction in Lp(a) levels,

Further research is needed to better understand the role of Lp(a) in disease development and to develop more targeted treatments. In the meantime, individuals with high Lp(a) levels should work with their healthcare providers to manage their overall risk for cardiovascular disease and related conditions.

You can also look up some of these phase III trials and see if you can get into a trial to get your numbers down.

As of today, we can recommend daily aspirin and reducing LDL cholesterol to below 40 mg/dL

Further Reading on Lipoprotein a:

https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2019/07/02/08/05/lipoproteina-in-clinical-practice

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/ATV.0000000000000147

Lipoprotein a References:

- Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A. Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Disease (Lancet, 2024).

- Reyes-Soffer G, Ginsberg HN, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein(a): A Genetically Determined, Causal, and Prevalent Risk Factor for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association (Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 2021).

- Schwartz GG, Ballantyne CM. Existing and Emerging Strategies to Lower Lipoprotein(A) (Atherosclerosis, 2022).

- Lacaze P, Bakshi A, Riaz M, et al. Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Relation to Lipoprotein(a) Genotypes (Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2022).

- Razavi AC, Bhatia HS. Role of Aspirin in Reducing Risk for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Individuals With Elevated Lipoprotein(A) (Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 2025).

- Bhatia HS, Trainor P, Carlisle S, et al. Aspirin and Cardiovascular Risk in Individuals With Elevated Lipoprotein(a): The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (Journal of the American Heart Association, 2024).

- Bhatia HS. Aspirin and Lipoprotein(a) in Primary Prevention (Current Opinion in Lipidology, 2023).

- Kosmas CE, Bousvarou MD, Papakonstantinou EJ, et al. Novel Pharmacological Therapies for the Management of Hyperlipoproteinemia(A) (International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023).

- Nissen SE, Linnebjerg H, Shen X, et al. Lepodisiran, an Extended-Duration Short Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Dose-Ascending Clinical Trial (The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2023).

- Lamina C, Kronenberg F, Lp(a)-GWAS-Consortium. Estimation of the Required Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapeutic Effect Size for Reduction in Coronary Heart Disease Outcomes: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis (JAMA Cardiology, 2019).

Still Have Questions? Stop Googling and Ask Dr. Alo.

You’ve read the science, but applying it to your own life can be confusing. I created the Dr. Alo VIP Private Community to be a sanctuary away from social media noise.

Inside, you get:

-

Direct Access: I answer member questions personally 24/7/365.

-

Weekly Live Streams: Deep dives into your specific health challenges.

-

Vetted Science: No fads, just evidence-based cardiology and weight loss.

Don't leave your heart health to chance. Get the guidance you deserve. All this for less than 0.01% the cost of health insurance! You can cancel at anytime!

[👉 Join the Dr. Alo VIP Community Today]