Dr. Alo's Dietary Guidelines Correcting The 2026 USDA Guidelines

Jan 19, 2026

The Actual Dietary Guidelines Approved By Cardiologist Dr. Alo

Comprehensive Dietary & Lifestyle Guidelines for Weight Management, Longevity, and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Based On The Consensus Of Scientific Literature

Based on the clinical framework of Dr. Mohammed S. Alo, DO, FACC and major peer-reviewed evidence and consensus statement and guidelines. (see References).

Many people are confused by the new Dietary Guidelines and Food Pyramid that were released by the Health And Human Services and the USDA because of conflicting messaging on social media and television that does not match what the guidelines actually say. Many of the suggested changes would worsen health outcomes.

They are also confused because the new "upside down" food pyramid appears to emphasize butter, steak, double cheeseburgers, lard, bacon, tallow, and fatty meals. This has been shown to increase morbidity and mortality and this is what got us to this place to begin with. The aim of Dr. Alo's "Cardiologist Approved Dietary Guidelines" is to correct the mistakes and over representations of the government guidelines with real evidence and data based on over 100 years of evidence and robust clinical trial data.

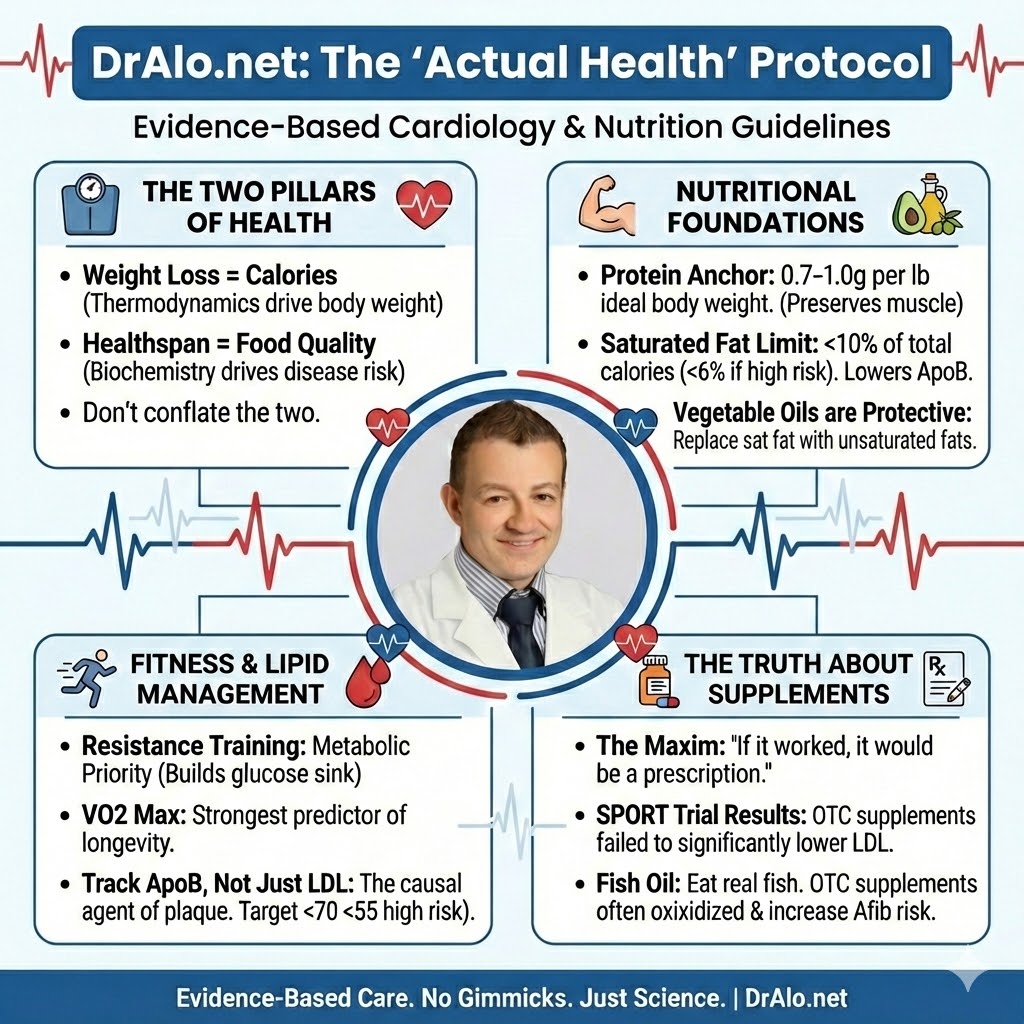

Here is a quick visual you can share:

How to use Dr. Alo's Dietary Guide

This protocol separates two different goals:

- Weight loss → driven primarily by energy balance (calories)

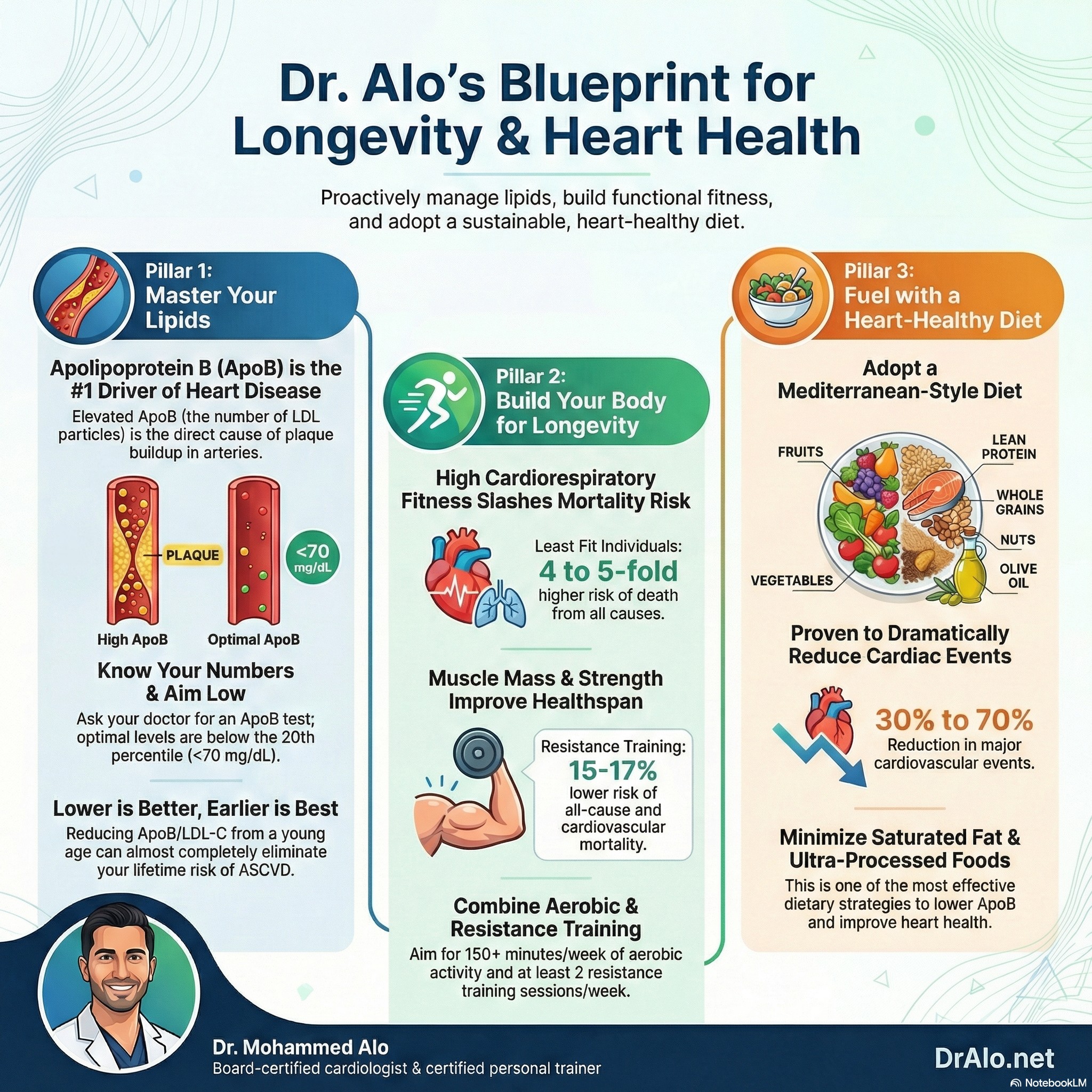

- Longevity / disease prevention → driven primarily by diet quality, lipid exposure (ApoB), blood pressure control, and lean mass preservation

You can lose weight eating almost anything if you maintain a calorie deficit. But you cannot reliably optimize long-term cardiovascular and metabolic health unless you also manage ApoB/LDL exposure, saturated fat, fiber, movement, and blood pressure.

Below is a summary infographic you can use as a New Dietary Guideline Summary:

Part I — The Actual Health Nutrition Hierarchy

1) Caloric awareness (for weight loss): Weight loss requires a sustained caloric deficit.

Simple starting estimate: Target body weight (lb) × 10 ≈ daily calories for weight loss (example: goal 180 lb → ~1,800 kcal/day). Adjust after 3 weeks.

Metabolic protection: Pair calorie reduction with resistance training and consider periodic diet breaks (maintenance calories) after prolonged dieting.

Note: Calorie needs vary by body size, activity, sleep, medications, and genetics. This formula is a starting point, not a prescription.

2) Protein (the metabolic anchor): Target 0.7–1.0 g per lb of ideal body weight/day minimum. You can target more if you are weightlifting and building muscle, usually up to 1.6 g per pound of lean body mass.

Why: Preserves lean mass during weight loss, improves satiety, and supports metabolic health.

Best sources: Egg whites, poultry breast, fish, nonfat Greek yogurt, whey/plant isolates, tofu, tempeh.

3) Saturated fat (the lipid lever): Keep saturated fat <10% of total calories; if higher risk or known ASCVD, aim for <6%.

Saturated fats are usually solid at room temperature.

Reduce these first: butter, cheese, lard, tallow, ghee, coconut oil, bacon/sausage, processed meat, fatty red meats (e.g., ribeye, ribs), full-fat dairy.

Why it matters: Saturated fat raises LDL/ApoB partly by reducing LDL receptor activity and increasing atherogenic particle exposure over time.

Fermented dairy, like Greek Yogurt, kefir cheese (labna) that is low in saturated fat appears to be neutral or slightly protective.

4) Prioritize unsaturated fats (including many seed and vegetable oils): Olive oil, avocados, nuts, seeds, and liquid vegetable oils such as canola/soy/sunflower/safflower.

These are usually liquid at room temperature.

Evidence summary: Replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats—especially polyunsaturated fats—lowers LDL-C and is associated with lower cardiovascular risk in human studies.

This is the easiest swap to reduce cardiovascular disease. Substituting saturated fat for unsaturated fats, in an isocaloric fashion, reduces LDL and cardiovascular disease rates significantly. Even very small swaps make a big difference. Even a replacement of 3-5% of your saturated fat intake, substituted for unsaturated (poly and mono unsaturated), can lower cardiovascular risk significantly.

5) Fiber & minimally processed carbohydrates: Emphasize soluble fiber (beans/lentils, oats, fruit) to support LDL lowering and glycemic control.

Practical approach: Build meals around vegetables/legumes/whole grains, then add lean protein and healthy fats. Aim for at least 30-40 g of fiber daily.

Sugar context: Added sugar is easiest to overconsume because it raises calorie density. The primary risk is caloric excess and weight gain, not “sugar as a toxin.”

Avoid refined sugars and highly processed foods, mainly due to their calorie density. They are usually highly palatable, high calorie, and easy to overconsume.

Part II — What to Do With Popular Diets

Mediterranean (gold standard): High in plants, legumes, nuts, olive oil; moderate fish/lean protein; low in ultra-processed foods and saturated fat. Best evidence for reducing cardiovascular events and mortality in randomized trials. The DASH Diet also falls into this category, it's the same as the Mediterranean diet, but no salt and no alcohol and is usually considered superior.

Keto / low-carb: Main risk is high saturated fat versions that can raise LDL-C/ApoB substantially in some people. If choosing low-carb, do Mediterranean-style low-carb using olive oil, nuts, avocado, fish, and keep saturated fat low. It's hard to keep these diets low in saturated fat, but it may be possible.

Carnivore: Avoid as a long-term health strategy. Eliminates fiber and many protective phytochemicals and often increases saturated fat exposure. Most carnivore dieters have increased LDL/apoB and insulin resistance as a result of this dietary pattern.

Intermittent fasting: A tool for calorie control—not a metabolic cheat code. Not consistently superior to continuous calorie restriction when calories are similar. Generally, more difficult to do and some evidence suggests that it is harder to build muscle on such diets.

Note: Regardless of which diet you do, it should be calorie controlled to maintain weight or weight loss, depending on goals.

Part III — Exercise: “Actual Fitness”

Resistance training (metabolic priority): ≥2 days/week. Use 8–10 exercises covering major muscle groups. General health/hypertrophy: 8–12 reps near-failure. Strength focus: 1–6 reps heavier sets. Progress using the “2-for-2” rule (increase load ~2–10%).

Why: Improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, function, frailty, muscle building, strength, and longevity markers.

Aerobic training + daily movement (longevity priority): 150 min/week moderate or 75 min/week vigorous. Start with 7,500+ steps/day (then build). VO₂ max is strongly linked with longevity; consistent training is the lever.

Read the "Actual Weight Loss" book, or download the Dr Alo App for a nice comprehensive exercise program for people of all levels. There is a beginner's program for the elderly, and at home only program with only two dumbbells, and a more advanced program for those who have access to a full gym.

Part IV — Cardiovascular Prevention & Advanced Testing

ApoB: ApoB reflects the number of atherogenic particles; discordance with LDL-C is not very common. You can use either one if you don't have apoB. ApoB measures total atherogenic particles in your blood stream.

Educational targets (individualize clinically):

- All comers: LDL or apoB < 100 mg/dL

- At least one risk factor: LDL or apoB < 70 mg/dL (risk factors include: male sex, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, obesity, sedentary, age over 45 for men, 55 for women, family hx of heart disease, etc)

- High risk / established ASCVD: ApoB ≤ 55 mg/dL (if you have already had a cardiovascular event)

- Very High Risk target LDL or apoB < 40 mg/dL (multiple ischemic events or elevated lipoprotein a)

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)]: Test once in adulthood at about age 18. If elevated, lower all other modifiable risks aggressively (ApoB, blood pressure, smoking). Your LDL or apoB goal in this case would be < 40 mg/dL.

CAC vs. soft plaque: CAC detects calcified plaque; CAC=0 lowers near-term risk but does not guarantee absence of early atherosclerosis. Treat based on lifetime exposure, not calcium score alone. Calcium is a late stage finding and we can avoid ASCVD if we suppress LDL/apoB for decades starting at a young age.

CCTA vs Soft Plaque: CCTA does not detect soft plaque unless it encroaches on the lumen of your arteries, in which case it is also a later stage finding. Keep apoB/LDL low to avoid ASCVD altogether.

Part V — The Truth About Supplements

Supplements:

- Alo verdict: “supplement the diet with food.” Use targeted supplements only when there is a clear indication (e.g., pregnancy folic acid, documented deficiencies, vegan possibly B12, iron, vitamin D, protein), ideally guided by labs and clinician oversight.

Multivitamins & antioxidants

- High-dose antioxidant supplementation has been linked to harm in some analyses (including increased all cause mortality with certain antioxidants).

- The USPSTF recommends against beta‑carotene and vitamin E supplementation for preventing cardiovascular disease or cancer. (increases all cause mortality)

- Routine multivitamin use has not demonstrated clear prevention of cardiovascular disease or cancer in the general population; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force finds insufficient evidence for benefit for most supplements.

Vitamin K2

- Alo verdict: don’t use K2 as a substitute for ApoB lowering, blood pressure control, and lifestyle fundamentals.

- Claims that K2 “pulls calcium out of arteries” or reverses coronary plaque are not supported by high-quality clinical evidence; trials to date have not shown reliable reversal of atherosclerosis or consistent reductions in coronary calcium scores.

- Vitamin K biology is interesting (it affects proteins involved in calcification), but controlled human outcome data are limited.

Red yeast rice

- Alo verdict: don’t use red yeast rice as a workaround for statins—if you need LDL/ApoB reduction, use standardized, evidence‑based therapies. Statins came from red yeast rice, you should take the regulated "real stuff". The supplements you buy from stores or online are not regulated, and 95% do not contain what the bottle says.

- Some products have been found to contain contaminants such as citrinin (a nephrotoxin) as well as liver toxins.

- In the U.S., products with “enhanced/added” lovastatin/monacolin K are considered unapproved drugs; consumers can’t reliably know potency or safety.

- Red yeast rice can contain monacolin K (chemically identical to lovastatin), but commercial products vary widely and labels typically don’t disclose monacolin content.

Niacin (vitamin B3)

- Alo verdict: niacin is not recommended at all for cardiovascular risk reduction in modern guidelines. It causes harm. The metabolites are inflammatory, it makes your HDL atherogenic, and causes acanthosis nigricans which is late stage diabetes)

- Harms in large trials included higher rates of adverse effects (e.g., infections, bleeding, liver toxicity) and worsened glycemic control in some participants.

- Niacin improves some lipid numbers (LDL down, HDL up), but major outcome trials did not reduce heart attacks or strokes when added to statin therapy.

Fish Oil

- Alo verdict: don’t use OTC fish oil as a substitute for proven lipid therapy; prioritize eating fish 1–2×/week and follow evidence‑based lipid management with your clinician.

- Even prescription, icosapent ethyl (Vascepa), which is a purified EPA product, has questionable outcomes and questionable benefit. (REDUCE‑IT). This should never be a first line agent in ASCVD or patient with high triglycerides. There are very rare scenarios where this is useful.

- Higher-dose omega‑3 formulations have been associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation in meta-analyses. This is for prescription and OTC formulations.

- Large randomized trials of standard OTC-style omega‑3 supplements have not shown consistent cardiovascular benefit for primary prevention (e.g., VITAL; STRENGTH).

- Over‑the‑counter (OTC) fish oil is a food supplement—dose and oxidation (rancidity) can vary by product; some independent testing has found label inaccuracy and high oxidation in certain markets.

- Even if they are not rancid, there has not been a definitive benefit.

Specific supplement myths (and the evidence-based take)

In the SPORT randomized clinical trial, researchers compared common “heart health” supplements to low‑dose rosuvastatin (5 mg) and placebo.

Cholesterol-lowering supplements: what the SPORT trial showed

- Low‑dose rosuvastatin lowered LDL‑cholesterol dramatically versus placebo and the supplements.

- Result: none of the supplements produced a meaningful LDL‑cholesterol reduction compared with placebo over the trial period. None beat placebo.

- Supplements studied included fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, CoQ10, and red yeast rice.

- Most supplement failed to lower LDL

- Cinnamon increased CRP (inflammation)

- More people on supplements quit due to side effects than the medication arm

Supplements Bottom Line

- Generally, most people do not benefit from supplements unless they have a clinically relevant deficiency or plan to be pregnant. Test for specific deficiency.

- Practical safety rule: treat supplements like medications—assume interactions are possible (especially with anticoagulants, blood-pressure meds, antiarrhythmics, and statins). Choose products that are third‑party tested (USP, NSF, Informed Choice) when possible.

- Supplements are regulated differently than drugs: most are not required to prove effectiveness before sale, and quality can vary by brand and batch. Most do not contain what the bottle says, and or, contain substances that are not listed on the package.

- Many effective drugs started as natural compounds—once proven, they were purified, standardized, and properly dosed (e.g., aspirin from salicylates; statins from fungal compounds; ACE-inhibitor development inspired by snake venom peptides, ozempic from lizard saliva, metformin from French lilac plant, digoxin from foxgloves leaves, coumadin from sweet clover, etc).

- Maxim: “If it worked, it would be a prescription medication.”

The “Billion Dollar Drug” rule

Dr. Alo’s operating principle on supplements is simple: if a product reliably prevented heart attacks or meaningfully lowered cholesterol or blood pressure, it would be regulated, standardized, and dosed like a prescription medication. Most known cardiovascular medications began as "supplements". Aspirin, coumadin, lisinopril, ozempic, metformin, digoxin, statins, etc. all began as naturally occurring substances We need to be able to regulate them and dose them, as some are deadly if not dosed correctly.

Part VI — Blood Pressure & Sodium

Sodium target: keep sodium <2,300 mg/day for most people; lower targets may benefit certain patients. If you have heart failure, below 1500 mg/day.

Salt substitutes: potassium-enriched salt substitutes reduced cardiovascular events in a large randomized trial. Citrus fruit like kiwis, oranges, limes, and lemons are a good source of potassium.

Safety note: Potassium salt substitutes are not appropriate for everyone (e.g., advanced kidney disease, certain medications). Ask your clinician.

Part VII — Special Topics

Dietary cholesterol (eggs, shrimp, “hyper-absorbers”): Saturated fat usually has a larger impact on LDL-C than dietary cholesterol, but high cholesterol intake may matter—especially at higher doses or in certain hyper responders (hyper absorbers).

Practical protocol:

- Egg whites: excellent protein source

- Egg yolks: if ApoB/LDL is elevated, reduce yolks and recheck labs

- If ApoB remains high despite low saturated fat, discuss absorption-targeted strategies (dietary cholesterol reduction; clinician-directed therapy such as ezetimibe)

- Dietary intakes over 300-400mg daily increase cardiovascular mortality as well as all cause mortality regardless of whether one is a hyper absorber or not.

Alcohol: Less is better for longevity. Alcohol is carcinogenic; risk rises with dose. Avoid drinking “for health.” It's a class 1 carcinogenic and should be avoided as much as possible. There is no benefit, and mostly harm.

Obesity, alcohol, and tobacco contribute to 74% of cancers. Avoid all three.

Part VIII — Hormonal Health & Cardiovascular Risk

Men (TRT): Lifestyle first (weight loss, sleep, strength training, minimize alcohol). In high-risk men with hypogonadism, TRAVERSE found TRT non-inferior to placebo for major adverse cardiovascular events, with monitoring needed for adverse signals. Split lower, and more frequent dosing, reduces thrombotic risk. Instead of taking 100 mg once a week, can split into 5 doses of 20 mg daily. Treat symptoms and labs. Men may have vastly different symptoms even at same blood levels.

Women (MHT): Used for symptom relief, not cardiovascular prevention. Timing and route matter; transdermal estrogen may have lower thrombotic risk than oral in several analyses. Individualize decisions clinically. You do not need labs to determine therapy decision (except for testosterone).

Treating thyroid and hormones will affect lipid panels (especially thyroid and estrogen) and hence, lipid lowering therapy decisions should be made once labs are stable. If lipids are very high, ten they should be on lipid lowering therapy regardless of hormonal state (can repeat later and adjust). Many patient will be on LLT long before hormonal issues arise, and should stay on LLT.

Transgender care: Hormone therapy can alter lipid profiles and risk markers. Apply the same evidence-based prevention tools: ApoB/LDL control, blood pressure control, smoking cessation, resistance training, metabolic optimization.

Part IX — Smoking Cessation

Smoking Cessation: Target Zero. Smoking is a direct endothelial toxin that accelerates atherosclerosis and increases thrombotic (clotting) risk. It negates many benefits of diet and exercise. Quitting is mandatory for longevity and reduces the risk of heart attack by 50% within the first year. Use Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) or prescription aids (Varenicline) if needed; the priority is eliminating combustion immediately. It's ok to switch to vaping if it will prevent smoke inhalation. Vaping is not as bad, and most patients will quit within a year.

Part X — Alcohol: Cardiovascular Risk, Cancer, and Longevity

Core Principle

Less alcohol is always better for health.

Alcohol is not a health food, not cardioprotective, and not required for longevity. Any perceived cardiovascular benefit at low doses disappears when modern confounders and cancer risk are properly accounted for.

Alcohol is a Group 1 carcinogen (same category as tobacco and asbestos), with risk increasing in a dose-dependent fashion.

Cardiovascular Effects

Blood pressure:

Alcohol raises blood pressure in a dose-dependent manner. Even modest intake increases hypertension risk and worsens BP control.

Arrhythmias:

Alcohol increases atrial fibrillation risk (“holiday heart syndrome”), even at low to moderate doses. Abstinence reduces AF recurrence.

Triglycerides & insulin resistance:

Alcohol raises triglycerides, worsens insulin resistance, and promotes visceral fat accumulation.

Heart failure & cardiomyopathy:

Chronic intake increases the risk of alcoholic cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

The “J-Curve” Myth (Why Older Studies Were Misleading)

Earlier observational studies suggested a J-shaped curve, where light drinkers appeared to have lower cardiovascular risk than abstainers. This has largely been explained by:

- Healthy user bias

- Inclusion of former heavy drinkers in abstainer groups

- Inadequate adjustment for socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors

When these confounders are addressed:

- No safe or beneficial dose remains

- Cardiovascular benefit disappears

- Cancer risk persists at all levels

Cancer Risk (Often Ignored)

Alcohol increases the risk of:

- Breast cancer (even 1 drink/day)

- Esophageal cancer

- Oropharyngeal cancers

- Liver cancer

- Colorectal cancer

Alcohol, obesity, and smoking together account for ~74% of cancers.

There is no threshold below which cancer risk is zero.

Practical Guidance

- Best for longevity: 0 drinks

- If you choose to drink:

- Keep intake as low and infrequent as possible

- Avoid daily drinking

- Do not drink “for health”

- Avoid binge patterns entirely

Wine is not protective. Any observed benefit is attributable to lifestyle confounding, not ethanol.

Alcohol & Weight Loss

Alcohol:

- Adds non-satiating calories

- Suppresses fat oxidation

- Lowers dietary restraint

- Disrupts sleep and recovery

It is one of the highest-impact levers to remove when fat loss stalls.

Bottom Line

- Alcohol is net harmful for cardiovascular health, metabolic health, cancer risk, and longevity

- There is no evidence-based reason to recommend alcohol for prevention

- Public messaging suggesting alcohol is “heart healthy” is outdated and incorrect

Optimal dose: zero.

Summary: “Actual Health” Targets (Educational)

|

Metric |

Practical Target |

|

Calories (weight loss start point) |

Target weight (lb) × 10 |

|

Protein Minimum |

0.7–1.0 g/lb ideal body weight |

|

Saturated fat |

<10% of calories (<6% higher risk) |

|

Sodium |

<2,300 mg/day (individualize) |

|

Steps |

≥7,500/day (build upward) |

|

Resistance training |

≥2 days/week |

|

Aerobic training |

150 min/wk moderate or 75 min/wk vigorous |

|

ApoB |

~70–80 mg/dL (lower risk); ≤55 mg/dL (high risk/ASCVD; individualize) |

|

Blood pressure |

Ideally <120/80 mmHg (individualize) |

|

Alcohol |

Best: 0 |

|

Smoking |

Best: None |

Disclaimer

This content is for education and is not medical advice. Discuss any major diet, medication, supplement, or exercise change with your clinician—especially if you have heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, pregnancy, or are taking prescription medications.

References

- Paluch AE, et al. Resistance Exercise Training in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease: 2023 Update (AHA Scientific Statement). Circulation. 2024. Link

- Paluch AE, et al. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public Health. 2022. Link

- Lee DC, et al. Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014. Link

- Ference BA, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2017. Link

- Borén J, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause ASCVD: EAS consensus. Eur Heart J. 2020. Link

- Sniderman AD, et al. Apolipoprotein B Particles and Cardiovascular Disease: A Narrative Review. JAMA Cardiology. 2019. Link

- Fernández-Friera L, et al. Normal LDL-C levels and subclinical atherosclerosis (PESA). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017. Link

- Estruch R, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet (PREDIMED). N Engl J Med. 2018. Link

- de Lorgeril M, et al. Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction (Lyon Diet Heart Study). Circulation. 1999. Link

- Iatan I, et al. Low-carbohydrate high-fat diet and incident CVD (UK Biobank). JACC Advances. 2024. Link

- Hooper L, et al. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease (Cochrane Review). 2020. Link

- Christensen JJ, et al. Dietary fat quality, atherogenic lipoproteins, and ASCVD. Atherosclerosis. 2024. Link

- Dayton S, et al. Diet high in unsaturated fat and complications of atherosclerosis (LA Veterans). Circulation. 1969. Link

- Marklund M, et al. Biomarkers of dietary omega-6 fatty acids and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality. Circulation. 2019. Link

- Neal B, et al. Effect of Salt Substitution on Cardiovascular Events and Death (SSaSS). N Engl J Med. 2021. Link

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. 2015. Link

- Pan A, et al. Red meat consumption and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012. Link

- Gu X, et al. Red meat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023. Link

- He FJ, et al. Salt Reduction to Prevent Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. Link

- Gardner CD, et al. Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet (DIETFITS). JAMA. 2018. Link

- Liu D, et al. Calorie restriction with or without time-restricted eating in weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2022. Link

- Zhong VW, et al. Dietary cholesterol or egg consumption and incident CVD and mortality. JAMA. 2019. Link

- Wood AM, et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption (599,912 participants). The Lancet. 2018. Link

- Voskoboinik A, et al. Alcohol abstinence in drinkers with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020. Link

- Nissen SE, et al. Cardiovascular safety of testosterone-replacement therapy (TRAVERSE). N Engl J Med. 2023. Link

- Rossouw JE, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin (WHI). JAMA. 2002. Link

- Hodis HN, et al. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal estradiol therapy (ELITE). N Engl J Med. 2016. Link

- Vinogradova Y, et al. Oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy and vascular events. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015. Link

- World Heart Federation. The Impact of Alcohol Consumption on Cardiovascular Health: Myths and Measures. 2022. Link

-

Bhatt DL, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Icosapent Ethyl (REDUCE‑IT). N Engl J Med. 2019.

-

NCCIH (NIH). Red Yeast Rice: What You Need To Know. Updated 2022.

-

The Health Consequences of Smoking: CDC / Surgeon General Report 2014

-

Benefits of Quitting Smoking: AHA/ACC Guideline on Lifestyle Management

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/cir.0000000000000678

- https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/03/17/new-guidelines-healthy-lifestyle-managing-risks-are-key-to-preventing-heart-attack-stroke

-

Wood AM et al., Lancet, 2018 — alcohol risk thresholds (599,912 participants)

-

Voskoboinik A et al., NEJM, 2020 — alcohol abstinence reduces AF recurrence

-

WHO / IARC — alcohol as a Group 1 carcinogen

-

World Heart Federation, 2022 — alcohol myths and cardiovascular risk

Still Have Questions? Stop Googling and Ask Dr. Alo.

You’ve read the science, but applying it to your own life can be confusing. I created the Dr. Alo VIP Private Community to be a sanctuary away from social media noise.

Inside, you get:

-

Direct Access: I answer member questions personally 24/7/365.

-

Weekly Live Streams: Deep dives into your specific health challenges.

-

Vetted Science: No fads, just evidence-based cardiology and weight loss.

Don't leave your heart health to chance. Get the guidance you deserve. All this for less than 0.01% the cost of health insurance! You can cancel at anytime!

[👉 Join the Dr. Alo VIP Community Today]