Even Rabbits Get Heart Disease (Here’s Why That Matters)

Jan 29, 2026

The Discovery Of Heart Disease In Rabbits Changed Everything We Know

The Mummies taught us a lot about heart disease, but the story didn't end there.

Fast forward a few million years.

Cholesterol was first discovered in 1769 by a French physician-chemist named François Poulletier de la Salle. He found it in gallstones, which are hard deposits that form in the gallbladder. But there was no connection to heart disease at this point.

In 1815, a French chemist named Michel Eugène Chevreul rediscovered cholesterol and named it "cholesterine." He also determined its chemical structure. At this point, there was still no link to heart disease. Chevreul is one of the 72 famous French scientists whose names are inscribed on the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Between 1907 and 1909, Alexander Ignatowski, who was involved in the laboratory of Nobel prize winner Ivan Pavlov, investigated whether a diet of excess protein was toxic and accelerated the ageing process. He fed rabbits large amounts of meat, eggs, and milk. It was indeed toxic for young rabbits, while adult rabbits developed atherosclerosis. As the latter was considered a hallmark of ageing, the hypothesis was proven according to Ignatowski.

Adolf Windaus reported in 1910 that plaques in aortas from atherosclerosis patients contained 20 times more cholesterol than normal aortas. While his PhD concerned Digitalis, he won the Nobel Prize in 1928 for his work on cholesterol.

In 1913 The Link Between Cholesterol And Heart Disease Solidified (pun intended)

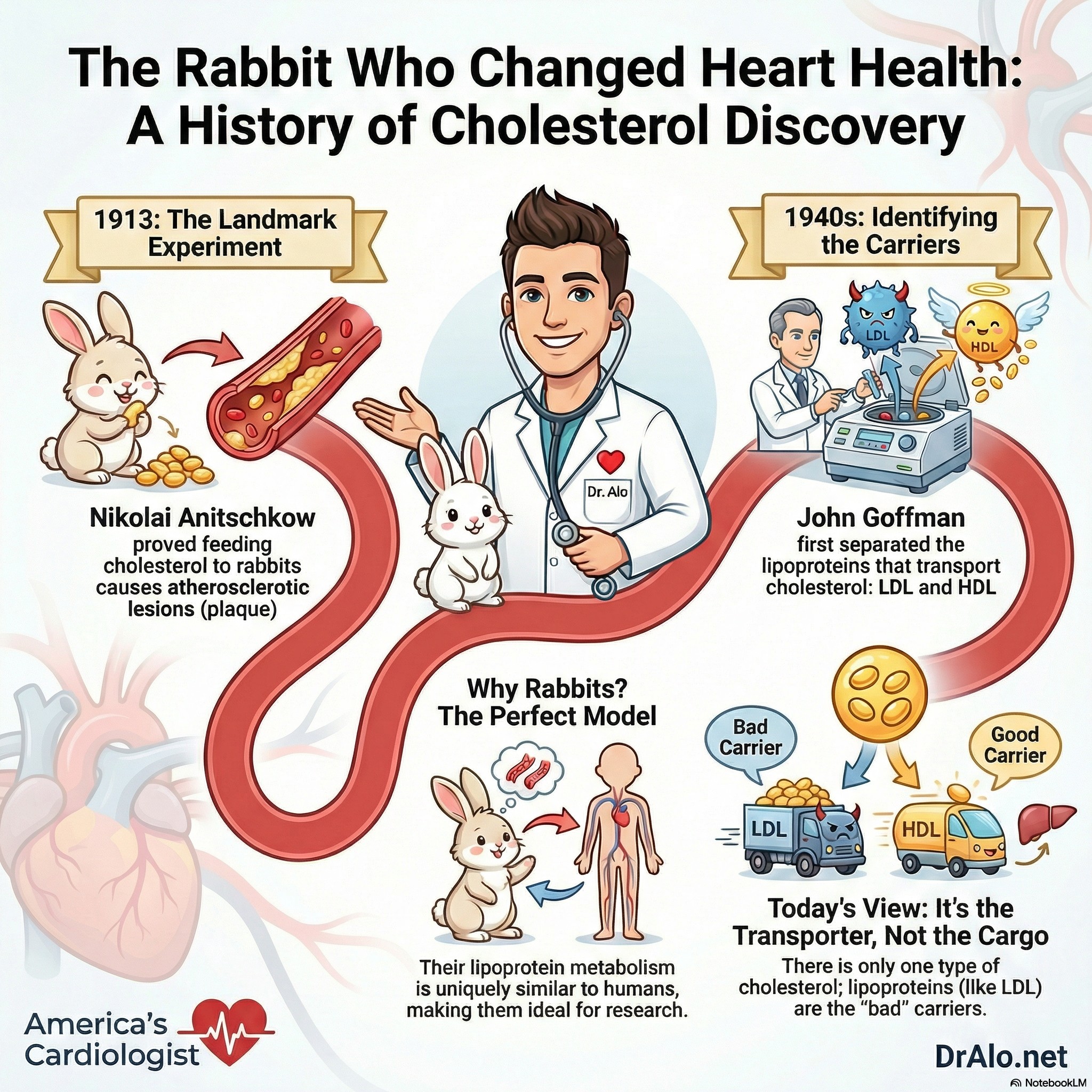

In 1913, Nikolaj Anitschkow discovered that a cholesterol fed rabbit would develop ASCVD if they had greatly elevated blood cholesterol levels. Rabbit arteries would turn out to be the one of the best animal models to study ASCVD in humans.

The foundation of modern atherosclerosis research was established over a century ago through a landmark discovery that fundamentally changed our understanding of cardiovascular disease. In 1913, Russian pathologist Nikolai N. Anitschkow demonstrated that rabbits fed a cholesterol-rich diet developed atherosclerotic lesions in association with greatly elevated blood cholesterol levels.[1] This seminal observation, made in St. Petersburg, established the participation of cholesterol in atherogenesis and introduced the cholesterol-fed rabbit as one of the most important animal models for studying human atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

Anitschkow's Groundbreaking Rabbit Discovery

Anitschkow's experimental approach was elegantly simple yet profoundly insightful. By feeding rabbits egg yolk, he induced the formation of fatty lesions in their arteries.[3] In contrast to other research groups at the time who were conducting experiments with protein-enriched diets, Anitschkow demonstrated that it was cholesterol alone that caused atherosclerotic changes in the rabbit arterial intima, which bore striking similarity to human atherosclerosis.

Through meticulous analysis of plaque development and histology, Anitschkow identified lipid-laden foam cells in experimental lesions, the hallmark of atherosclerosis that remains central to our understanding today. He characterized the key cell types that modern atherosclerosis research continues to focus on using advanced immunohistochemical methods: smooth muscle cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes. Furthermore, he distinguished between early lesions (fatty streaks) and advanced lesions (atheromatous plaques), establishing a framework for understanding disease progression.[2]

By standardizing cholesterol feeding protocols, Anitschkow discovered that the amount of cholesterol uptake was directly proportional to the degree of atherosclerosis formation.[2] His explanation for this observation aligned with what modern terminology calls the "response-to-injury" hypothesis of atherosclerosis.

The Rabbit as an Atherosclerosis Model

Rabbits represent the initial species in which experimental atherosclerosis was induced, and they have remained a cornerstone of atherosclerosis research for over a century.[4] The enduring value of this model stems from several unique features that make rabbits particularly well-suited for studying human lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis.

Lipoprotein Metabolism Similarities

Rabbits possess unique features of lipoprotein metabolism that are similar to humans but unlike rodents.[5-6] They express cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), similar to humans, and have a lipoprotein profile that more closely resembles human physiology than that of mice or rats. This phylogenetic proximity to humans, combined with their sensitivity to dietary cholesterol, makes rabbits an excellent species for examining aspects of human cardiovascular disease.

When fed a cholesterol-enriched diet, rabbits develop severe hypercholesterolemia due to marked increases in hepatically and intestinally derived remnant lipoproteins, called β-very low density lipoproteins (VLDL), which are rich in cholesteryl esters. This metabolic response facilitates the development of atherosclerotic lesions that progress from foam cell accumulation to advanced plaques with features resembling human disease.

Practical Advantages Of Bunnies

Beyond their physiological similarities to humans, rabbits offer several practical advantages as research subjects. They have relatively short life spans, short gestation periods, high numbers of progeny, and lower costs compared with other large animals such as dogs, pigs, and monkeys. Their proper size, tame disposition, and ease of maintenance in laboratory facilities make them accessible for a wide range of experimental designs. These characteristics allow rabbits to serve as a bridge between smaller rodents and larger animals, playing an important role in translational research activities such as pre-clinical testing of drugs and diagnostic methods.

Types of Rabbit Models

Currently, three types of rabbit models are commonly used for studying human atherosclerosis and lipid metabolism:[6]

- Cholesterol-fed rabbits: The most common model involves feeding New Zealand White rabbits a cholesterol-enriched diet, which induces atherosclerotic lesion formation similar to Anitschkow's original experiments.

- Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic (WHHL) rabbits: These rabbits exhibit familial hypercholesterolemia due to genetic deficiency of LDL receptors, analogous to human familial hypercholesterolemia. WHHL rabbits develop progressive intimal lesions, fatty streaks, raised foam cell lesions, and atheroma in the aorta and coronary arteries, with lesions that can progress to advanced human-like atherosclerosis.

- Genetically modified rabbits: Recent advances have enabled the creation of transgenic and knockout rabbits, expanding experimental possibilities.

Applications in Modern Research

The cholesterol-fed rabbit model can be used to investigate numerous pathophysiological aspects that contribute to human atherosclerosis, including lipoproteins, diabetes, mitogens, growth factors, adhesion molecules, endothelial function, receptor pathways, and platelets. The model can be combined with various methods that cause endothelial dysfunction and injury, such as balloon denudation, electric stimulation, cuff implantation, artificial hypertension, diabetes, or infection.

Recent genomic and transcriptomic analyses of hypercholesterolemic rabbits have revealed many differentially expressed genes in atherosclerotic lesions and livers, including genes involved in inflammation and lipid metabolism regulation. The completion of rabbit genome sequencing and transcriptomic profiling of atherosclerosis has paved new ways for researchers to use this model in future investigations.

Historical Context and Legacy

For many years following Anitschkow's initial observations, his work received little recognition. However, the combination of experimental work, autopsy studies, epidemiological investigations, and clinical trials eventually led to firm establishment of the essential role of lipids in atherosclerosis. The cholesterol hypothesis gained further support from Adolf Windaus's demonstration of cholesterol in atherosclerotic plaques and Carl Müller's identification of a hereditary condition with elevated plasma cholesterol and premature myocardial infarction.

The severity of hypercholesterolemia, extent of LDL receptor expression downregulation, and aortic root localization of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits strikingly resemble the cardinal features of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in humans, suggesting that the former is a phenocopy of the latter. This resemblance corroborates Anitschkow's concept that "Cholesterin ist alles" (Cholesterol is everything).

Anitschkow's Rabbit ASCVD Discovery In 1913

Nikolai N. Anitschkow's 1913 discovery that cholesterol feeding induces atherosclerosis in rabbits laid the foundation for more than a century of cardiovascular research. The cholesterol-fed rabbit model has provided invaluable insights into the pathogenesis and development of human atherosclerosis and has made substantial contributions to translational medicine. Despite the development of numerous other animal models, including genetically modified mice, rabbits continue to play a vital role in atherosclerosis research, bridging the gap between basic science and clinical application. The enduring relevance of this model stands as a testament to Anitschkow's brilliant experimental insight and his fundamental contribution to our understanding of human vascular disease.

When Was Diet Linked To Heart Disease?

As early as 1916, it was discovered that diet plays a role in cholesterol levels. A scientist named Cornelis de Langen observed that people from Indonesia had much lower cholesterol levels compared to Dutch colonists. In 1922, he conducted a study to see how diet affects cholesterol. He found that when Indonesians ate a "Dutch diet" high in eggs and meat for three months, their cholesterol levels increased by an average of 27%. Indonesians who had moved to Amsterdam had the same high cholesterol levels as the Dutch.

Discovering Chylomicrons & Lipoproteins

In 1924, scientists Simon Henry Gage and Pierre Augustine Fish discovered tiny particles called chylomicrons in human blood after a fatty meal. These particles were about 1 µm in size. Another scientist, Heinrich Wieland, received the Nobel prize in 1927 for his important research on bile acids and sterols.

In the late 1940s, John Goffman was the first to separate and further identify lipoproteins using a centrifuge and labeled particles as to their density: very low density, intermediate density, low density, and high density (VLDLs, IDLs, LDLs, HDLs).

In 1939, Arne Tiselius was the first to discover that cholesterol and phospholipids do not circulate freely in plasma (like glucose), but travel bound to alpha and beta, but not gamma proteins, which subsequently were named alpha and beta lipoproteins.

Those With High Cholesterol Had More Heart Attacks

The link between cholesterol and heart disease was again suspected in the 1950s, when researchers found that people with high cholesterol levels in the blood were more likely to have heart attacks. That’s when things started to clear up.

The Discovery Of LDL and HDL

In the 1960s, we discovered that there are two main types of cholesterol: LDL cholesterol, or what was called "bad" cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol, or what they thought was "good" cholesterol. Obviously, we don’t call it good or bad anymore, but the names have stuck around, and we still use them when explaining cholesterol to patients. As an aside, there is no reason to call HDL cholesterol, "good". There is no correlation with any "good" functionality. Having higher or lower levels of HDL-C does not confer protection nor benefit. HDL cholesterol is not cardioprotective, like we used to think, It is a number that can largely be ignored.

Is Cholesterol really Bad?

Cholesterol is just cholesterol. There is only one cholesterol molecule. It is neither good nor bad. The lipoprotein that the cholesterol is transported inside of, has been for decades, described as either good or bad depending on the role it is carrying out at the time. The role can change throughout its lifecycle. These are called lipoproteins. If lipoproteins participate in reverse cholesterol transport, they are generally considered good. Because of epidemiological data that linked LDL cholesterol to ASCVD risk and HDL cholesterol to protection from ASCVD the particles were respectively called "bad" and "good."

References

- Buja LM. Nikolai N. Anitschkow and the Lipid Hypothesis of Atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2014;23(3):183-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24484612

- Finking G, Hanke H. Nikolaj Nikolajewitsch Anitschkow (1885-1964) Established the Cholesterol-Fed Rabbit as a Model for Atherosclerosis Research. Atherosclerosis. 1997;135(1):1-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9395267

- Libby P, Hansson GK. From Focal Lipid Storage to Systemic Inflammation: JACC Review Topic of the Week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;74(12):1594-1607. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31537270

- Daugherty A, Tall AR, Daemen MJAP, et al. Recommendation on Design, Execution, and Reporting of Animal Atherosclerosis Studies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2017;37(9):e131-e157. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28729366

- Fan J, Niimi M, Chen Y, Suzuki R, Liu E. Use of Rabbit Models to Study Atherosclerosis. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2022;2419:413-431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35237979

- Fan J, Kitajima S, Watanabe T, et al. Rabbit Models for the Study of Human Atherosclerosis: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Translational Medicine. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2015;146:104-19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25277507

- Fan J, Chen Y, Yan H, et al. Principles and Applications of Rabbit Models for Atherosclerosis Research. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 2018;25(3):213-220. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29046488

- Fan J, Chen Y, Yan H, et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of Hypercholesterolemic Rabbits: Progress and Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(11):E3512. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30413026

- Thompson GR. Atherosclerosis in Cholesterol-Fed Rabbits and in Homozygous and Heterozygous LDL Receptor-Deficient Humans. Atherosclerosis. 2018;276:148-154. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30064057

- Shapiro MD, Maron DJ, Morris PB, et al. Preventive Cardiology as a Subspecialty of Cardiovascular Medicine: JACC Council Perspectives. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;74(15):1926-1942. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31601373

Still Have Questions? Stop Googling and Ask Dr. Alo.

You’ve read the science, but applying it to your own life can be confusing. I created the Dr. Alo VIP Private Community to be a sanctuary away from social media noise.

Inside, you get:

-

Direct Access: I answer member questions personally 24/7/365.

-

Weekly Live Streams: Deep dives into your specific health challenges.

-

Vetted Science: No fads, just evidence-based cardiology and weight loss.

Don't leave your heart health to chance. Get the guidance you deserve. All this for less than 0.01% the cost of health insurance! You can cancel at anytime!

[👉 Join the Dr. Alo VIP Community Today]